Andy Warhol, 6 "Dollar Signs" 1981, 1981

While the trendy taboo in 2022 is talking about Bruno, a much more established and deeply engrained rule (particularly in American culture) is that ‘we don’t talk about money’. [For those interested in exploring how this taboo manifests more deeply, I highly recommend Joe Pinsker’s analysis in The Atlantic, which explores how the taboo varies by class, job and circumstance, and how various societal proxies allow us to talk about money and decipher socioeconomic and class positions without ever actually talking about numbers – in short, even though we don’t ever talk about money, we’re often talking about money].

In my very conservative household growing up, we rarely spoke about money, but that didn’t mean it wasn’t a significant part of our family’s moral matrix. In fact, by a very young age I had internalized several of my (fiscally) conservative parent’s attitudes towards it, and their ‘rules’ about money that have deeply informed my relationship with it today.

Rule #1: Never discuss finances outside of the nuclear family.

Never ask someone how much something cost – their dress, their car, their vacation, anything. It’s rude and it’s none of my/your business. Further, it’s no one’s business how much you/we make, how much you/we have, how expensive something you/we have is, etc. And if someone asks any of those questions pointedly, respond vaguely and when in doubt, downplay.

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.” ― Charles Dickens, David Copperfield

Rule #2: Always live within your means, and save for a rainy day.

My mother was raised in a tenement building on the Lower East Side of New York City in the 50s by immigrant parents who had lived through The Great Depression, so her views on money came from not having any. As such, she didn’t believe in purchasing anything you couldn’t afford in full—even on a credit card, if you couldn’t—and she wanted to save two dollars for every one that she sent for a rainy day when unexpected expenses might pile up.

Barbara Kruger, Installation view, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, 2012.

“Money is a great servant but a bad master.” ― Francis Bacon

“Don't think money does everything or you are going to end up doing everything for money.” ― Voltaire

Rule #3: Be grateful for whatever you have.

When I learned about economic classes in school, I asked my father which we were and he said that we were the best place to be, in the middle—with plenty of people who have more than we do, and others who sadly had less. He warned me not to put too much weight on such things, and more importantly, not to feel envy when I encountered those with more, nor pride when I saw someone with less, but instead let the fact that some of my friends had more keep me humble, and the fact that others had less keep me grateful.

“A man wants to earn money in order to be happy, and his whole effort and the best of a life are devoted to the earning of that money. Happiness is forgotten; the means are taken for the end.” ― Albert Camus, The Myth of Sysphus and Other Essays

Rule #4: Money buys things (and can fix some problems), but it does not buy happiness.

It’s easy to say money isn’t ‘everything’ or that it ‘doesn’t matter’ cavalierly when you have it. Money, absolutely matters. Without it and the basic necessities it can provide, life is exponentially tougher. When money is scarce, it’s all-too-easy to believe that if you only had money, everything would be okay. But, some of the most unhappy people I know have an abundance of money because unfortunately, money can buy just about anything, but it can’t buy happiness.

“Simple, genuine goodness is the best capital to found the business of this life upon. It lasts when fame and money fail, and is the only riches we can take out of this world with us.” ― Louisa May Alcott, Little Men

Rule #5: Every THING is replaceable, people are not.

When my parents were a young married couple, they lost everything in a fire. From then on, they believed and imparted the belief to me that things are replaceable, and even objects we love that are linked to memories and nostalgia that perhaps aren’t replaceable, are inconsequential compared to the only thing that truly matters, people. As such, I was raised not to value things (or the money that enabled us to purchase them), but instead value people—relationships, memories, experience—the things that money cannot buy, and that which truly yields happiness.

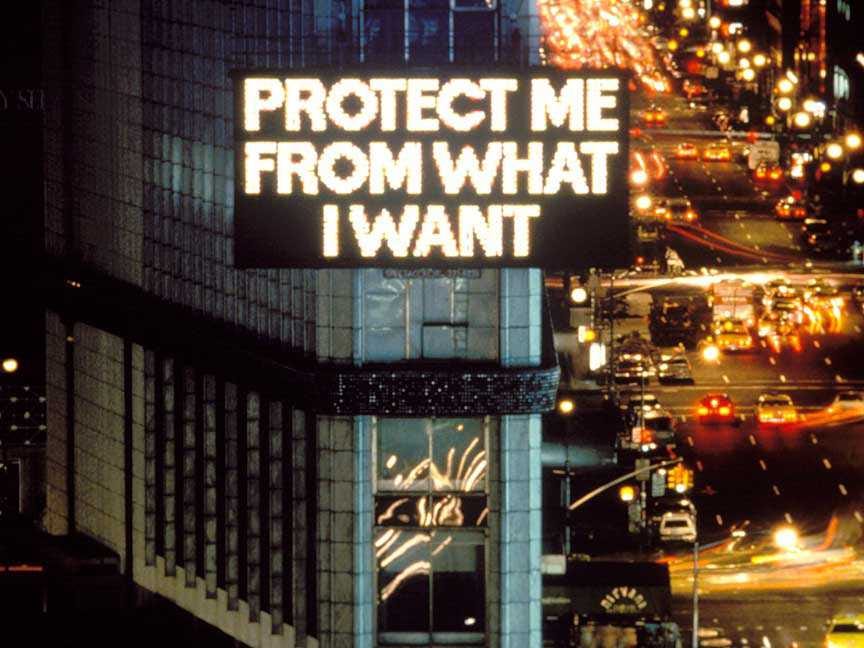

Jenny Holzer, from Survival (1983–85), © 1985 Photo: John Marchael

“Wealth is like sea-water; the more we drink, the thirstier we become; and the same is true of fame.” –Arthur Schopenhauer

We live in a world that is obsessed with money, power, and fame. Before children have even begun to explore the many facets of their identity—their talents, their interests, their beliefs and ultimately, their purpose—we’re already asking them what they want to be and shepherding them towards careers that will bring them wealth, power, and fame—doctors, lawyers, a celebrity, even, President of the United States. And, my parents—despite the many sound perspectives noted above—were no different. They strongly discouraged me from pursuing an art history degree because there wasn’t an obvious path to financial success thereafter, and they believed that was an important consideration when choosing a career path. There certainly isn’t anything wrong with being practical and seeking a career that will yield us financial independence—far from it – but the danger here is in making decisions, and teaching children to make decisions that are exclusively motivated by money. As Voltaire cautioned, “Don't think money does everything or you are going to end up doing everything for money.”

As with most things in life, ‘money’ in and of itself is not the problem. Despite the anti-capitalist narrative, money is not inherently evil, but rather intrinsically neutral. It’s simply a societally agreed upon medium of exchange—an object (increasingly a digital rather than physical one, but nonetheless) that we’ve assigned an arbitrary ‘value’ to in order exchange goods and services. However, when we begin to ‘overvalue’ money in our lives and are willing to sacrifice our morals and ethics to attain (or keep it), that is when money becomes tainted or evil.

We are raising children in a society that places too much importance on money, power, and fame—so of course, they are growing up to be greedy, self-centered, power-hungry adults. We must reshape our values, and subsequently the formal and informal education our children received. As the brilliant W.E.B. DuBois opined, if we make money the primary goal, then we shall develop money-makers but not necessarily good people, instead we must focus on “intelligence, broad sympathy, knowledge of the world that was and is, and of the relation of men [and women] to it—this is the curriculum of that higher education which must underlie true life.”